Concurrency and Kotlin

When I was first introduced to a Kotlin codebase, there were a lot of terms scattered throughout the project; suspend, runBlocking, Flow just to name a few.

I didn’t know what most of these meant or why they were used so I thought I’d do a little investigating. After a bit of research and chatting to some colleagues it turns out it was all about concurrency and coroutines!

This article aims to give you an introduction to the world of concurrency, how computers enable concurrent processes, and demystify a lot of the concurrency tools available in Kotlin.

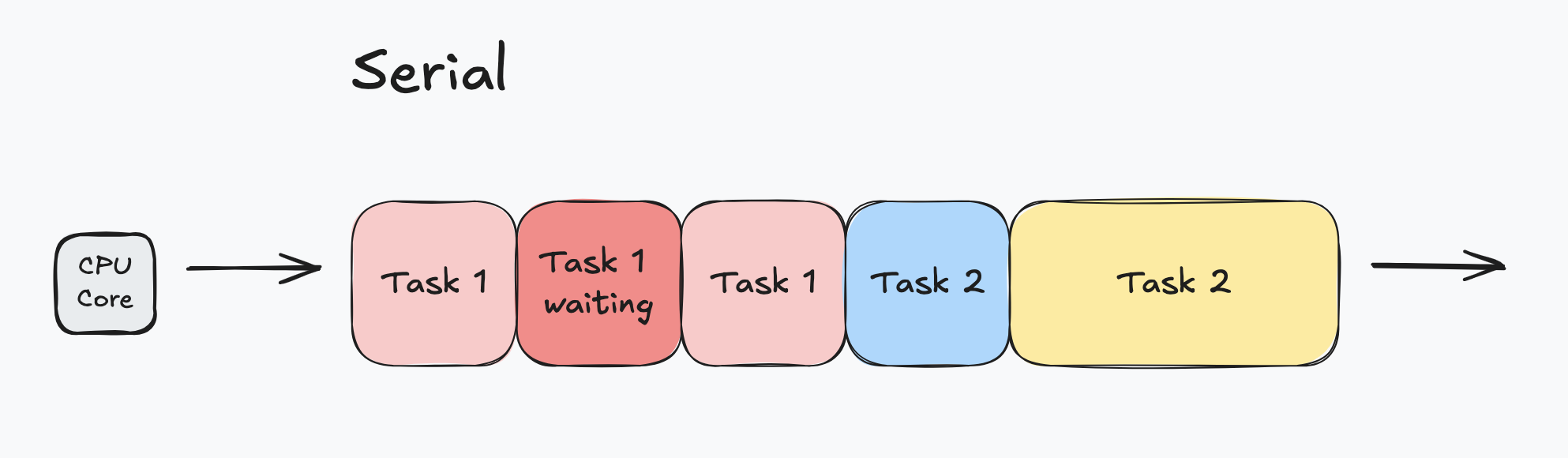

What’s the difference between serial, concurrent, and parallel tasks?

This question usually comes up when talking about concurrency so let’s get this out of the way.

Serial tasks are executed one at a time. When one task is completed, the next task begins.

When a task is blocked (e.g. waiting for an API response), nothing is being executed.

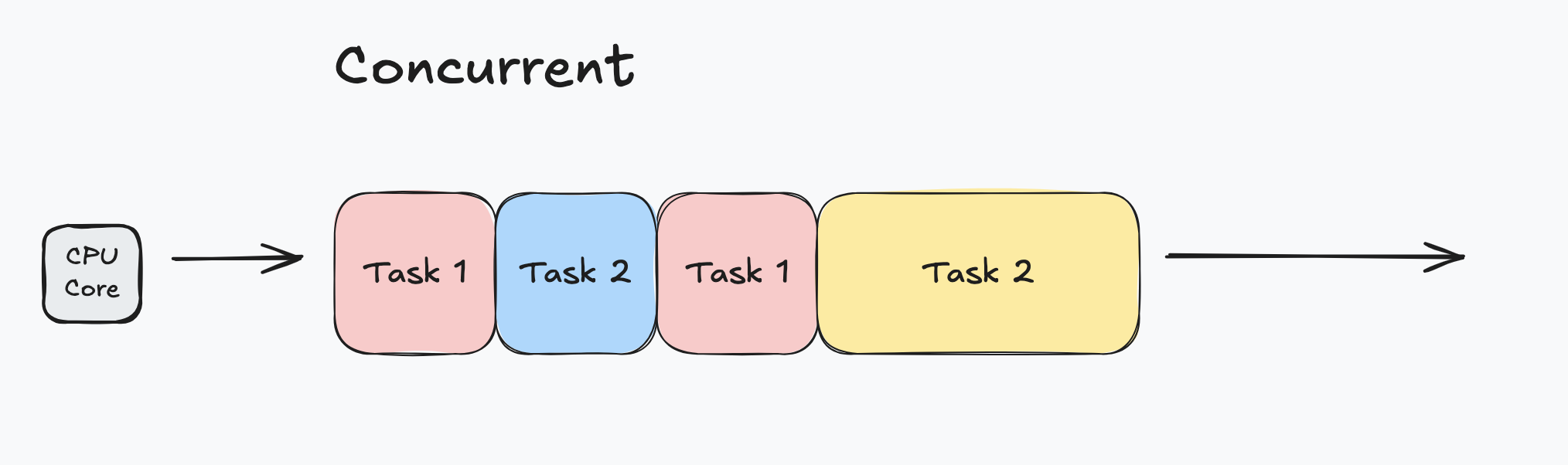

Concurrent means tasks are still only executed one at a time, but this time execution is interleaved between tasks.

This is particularly useful as when one task is blocked, another task can begin execution in the meantime.

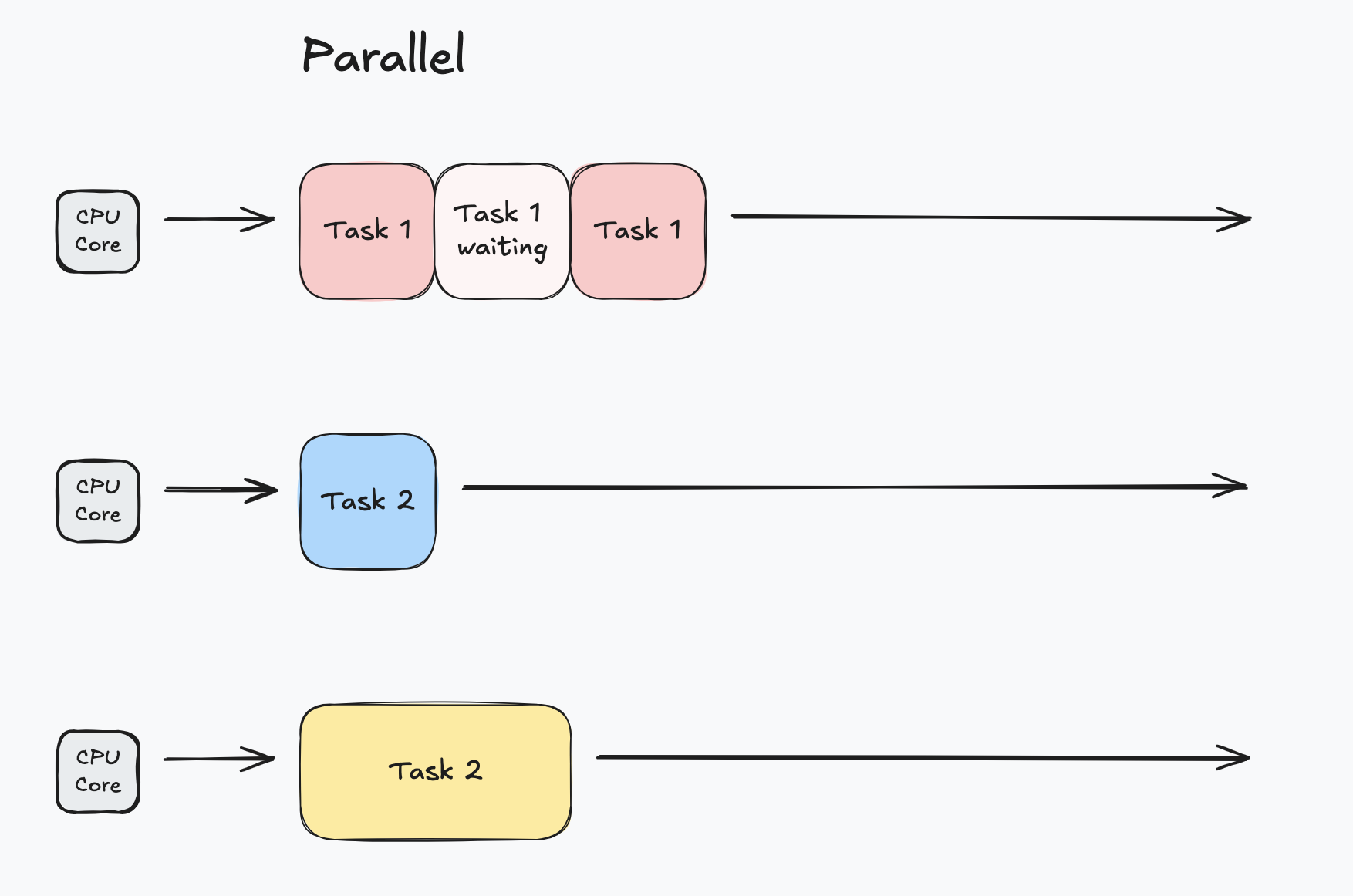

Parallel means multiple tasks are executed at the same time. Completing all tasks only take as long as the longest running task. Parallel execution requires multiple processing units to run in parallel.

For the most part, we will be talking about concurrent processes here.

Threads, processes, and the CPU

The CPU

Before we get into how concurrency works in Kotlin, let’s establish a basic understanding of how computers enable concurrency.

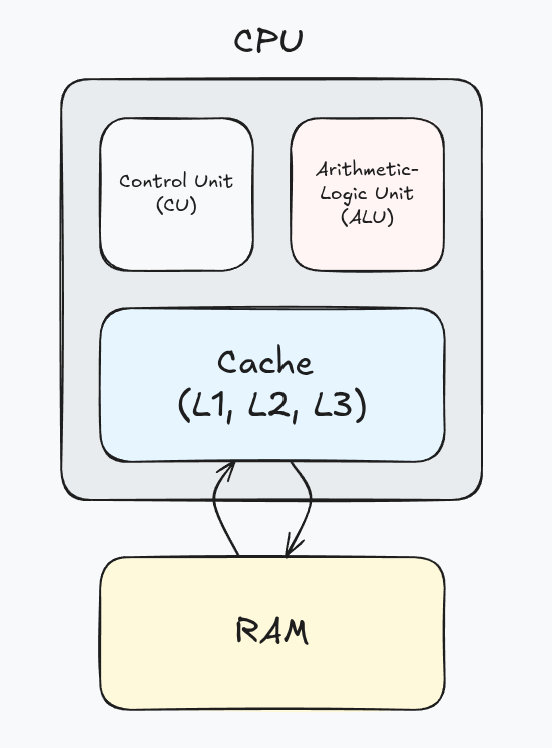

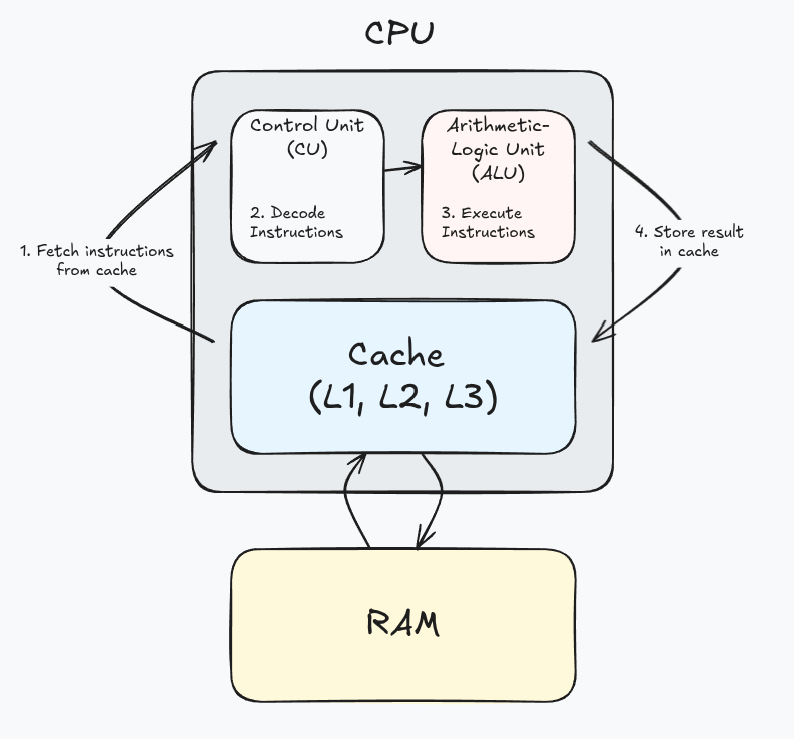

The Central Processing Unit (CPU) is responsible for executing all* of the instructions of our programs.

The CPU is made up of:

- the Control Unit (CU), which interprets machine instructions

- the Arithmetic-Logic Unit (ALU), which performs arithmetic and bitwise operations sent from the CU

- the cache, which stores temporary memory for quick access to information

When processes are started up, its program instructions and data are loaded into RAM, then into the CPU cache as needed. The cache controller is responsible for managing what data is in the cache predicting what program data should be added next.

CPU execution cycles

The CPU is always performing a continuous execution cycle of 4 stages:

- Fetch instruction from cache

- Decode the instruction

- Execute the instruction

- Store the result of the instruction

In a single core computer, all instructions are run serially. The CPU doesn’t have a concept of “processes” or “threads”. This is managed beyond the hardware layer.

That is a woefully basic description of the CPU, there’s a lot more going on but for our sake this is enough detail to continue.

If you’re reading this article you’re probably familiar with the “other PU”, the GPU. This is also responsible for executing instructions and is incredibly fast due to its massive amounts of cores which enable parallelism however GPUs have far limited instruction set compared to CPUs so they can only perform a limited set of tasks, like BitCoin mining

Processes

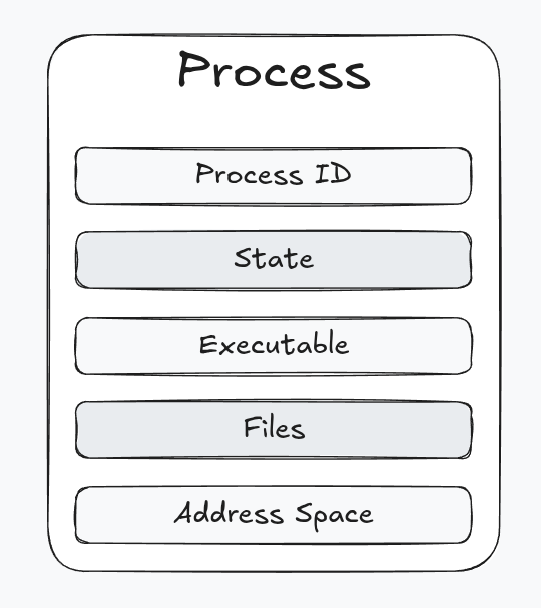

A process is simply a running program. It is a set of instructions waiting to be executed.

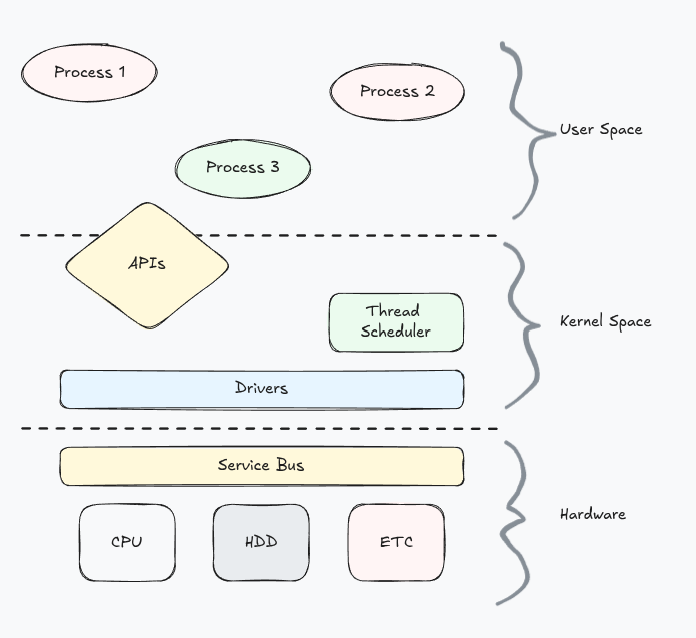

Most of the programs we build never need to directly interface with the hardware running on a computer. The operating system (aka kernel space) is responsible for those operations.

Instead, most software runs above the operating system as an isolated process in User Space and uses the APIs provided by the OS.

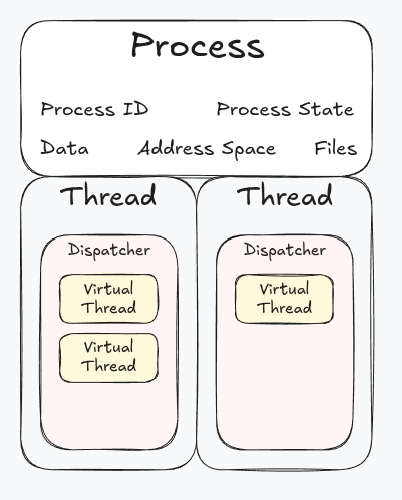

Processes share hardware resources which are managed by the OS. To facilitate this, processes are given their own independent address space and file table.

Properties of a process

- Process ID (PID)

- Process state - created → ready ↔ running → terminated

- Executable - The executable file containing the machine instructions

- Files required by the process

- Address space of the process

In general, processes are completely independent and isolated from each other, which can make communication between processes challenging.

While processes can spawn their own child processes, these child processes are still independent from the parent process and cannot directly communicate.

Spawning child processes from a parent process is a method of achieving concurrency however these processes cannot directly communicate

Threads

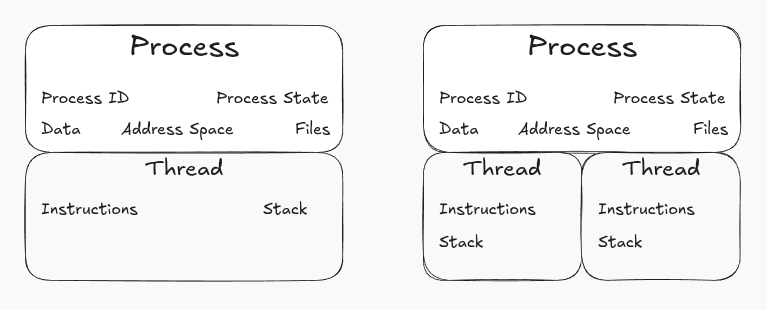

A thread is an independent stream of instructions the execution of which is managed by the OS.

Processes can spawn multiple threads to execute instructions concurrently. These threads share the resources and memory space of the process they’re created in which simplifies sharing resources between threads.

With the introduction of threads, the process can be viewed as the container for the process resources (address space, active connections, etc) and the thread the container of the process instruction set.

Threads are managed in the kernel space via a scheduler which allocates CPU time to thread execution.

Thread management is limited by the number of CPU cores as the more threads per CPU core the more time the kernel will need to spend scheduling each thread, which is time not spent executing threads.

Virtual threads

Virtual threads act in the same way as traditional threads but are managed by the process in user space. These require less overhead than traditional threads which allows for many more virtual threads to run at the same time.

When a traditional thread is blocked the underlying OS thread is also blocked, which prevents its use from other resources.

When a virtual thread is blocked, it is considered suspended. Its state is stored and the underlying OS thread is freed up to execute other scheduled virtual threads.

Concurrency in Kotlin

OK. With all that out of the way, let’s get into the code! Concurrency is enabled in Kotlin via the use of traditional threads and virtual threads, known as coroutines.

Coroutines can be created and managed via the Kotlin standard library, but most projects use the official kotlinx-coroutines library for it’s intuitive coroutine builders, so these examples will be using that library.

Suspend functions

When working in a Kotlin project you will see a lot of function definitions with the suspend keyword about.

suspend functions can only be called in a coroutine context. As the name suggests, this enables the function to be suspended in which the current context stops executing and the coroutine state is saved, allowing the underlying thread to execute another coroutine.

suspend fun foo() {

bar()

// this is a suspension point

yield()

baz()

}

In the above example foo is a suspending function. It can call other suspending functions just the same as any non-suspending function.

Here, it is calling yield, a suspend function provided by the kotlinx library which suspends the current coroutine and immediately schedules it so the next scheduled coroutine can execute.

Calling suspend functions in a coroutine context wont run concurrently by default. For that we need some additional coroutine builders.

Launching a coroutine

launch creates a new Job and runs it concurrently so it doesn’t block the current execution context. When run within a coroutine scope (which is a blocking operation) the scope will not exit until all launched Jobs have completed.

// create a coroutine context

// this blocks the underlying OS thread until

// all jobs have completed

runBlocking {

// launch a new job (coroutine) so that it can be run

// concurrently in the current coroutine scope

launch {

println("task 1 step 1")

// suspend the current job and immediately schedule it

// for when the thread becomes available

yield()

println("task 1 step 2")

yield()

println("task 1 step 3")

}

launch {

println("task 2 step 1")

yield()

println("task 2 step 2")

yield()

println("task 2 step 3")

}

}

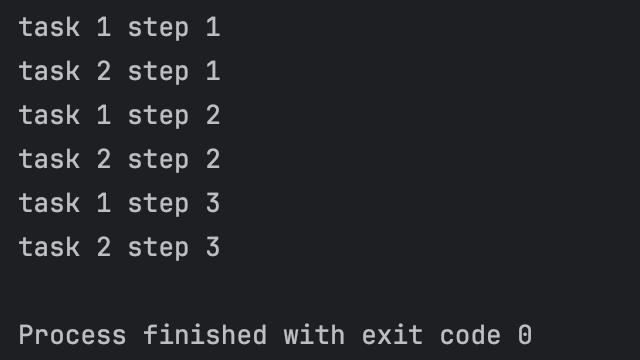

In the above example, we created a coroutine context with runBlocking witch enables the use of coroutine functions.

Inside that context, we launched two coroutines which each printed out a line before yielding to the other coroutine.

See here for the full code.

Waiting for the Job to complete (join)

Often you may want to run multiple Jobs concurrently, and only run other tasks once the previous jobs are completed.

For this you can use the join method from the launched job which suspends the coroutine until the job has completed.

Take the following code:

// create a coroutine context

runBlocking {

// launch a new job to run concurrently

val job1 = launch {

// suspend the current coroutine for 100ms

delay(100)

println("job 1 complete")

}

// launch a new job to run concurrently

val job2 = launch {

delay(50)

println("job 2 complete")

}

// suspend until all jobs have completed

joinAll(job1, job2)

println("all jobs completed")

}

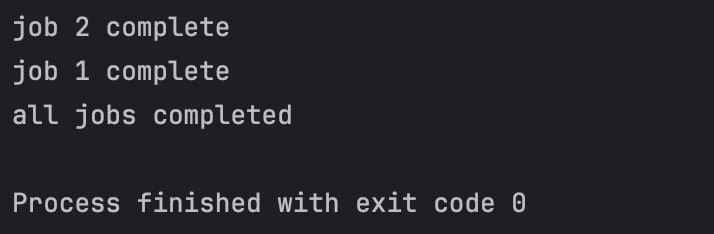

Which produces the output:

Another method of achieving this is to launch the jobs in a new coroutineScope which creates a new coroutine context, inheriting the existing context, and suspends the current coroutine until all jobs in its scope have completed.

// create a coroutine context

runBlocking {

// suspend until jobs have completed

coroutineScope {

launch {

delay(100)

println("job 1 complete")

}

launch {

delay(50)

println("job 2 complete")

}

}

println("all jobs completed")

}

See here for the full code.

Returning values from a Job (async)

async operates similar to launch however this returns a Deferred object. Deferred objects are a type of future object.

A future object is a “promise” that at some point a value will be returned, or an error will be thrown. To access the result you can call await the result which will suspend the current coroutine until the result or error is available.

// create coroutine context

runBlocking {

// async is a coroutine builder which launches a Job

// and returns a Deferred object.

// A Deferred object will eventually return a result, or it will fail

//

// taskOne immediately suspends the current job

// before returning "world"

val taskOne = async {

yield()

" world"

}

// taskTwo immediately returns "hello"

val taskTwo = async {

// uncommenting the two lines below will also cancel the

// job awaiting the result from taskTwo

// cancel()

// yield()

"hello"

}

// await the results in another coroutine so we don't block

launch {

// await suspends the current coroutine

// until the result is available.

// if the job was cancelled then this job will also be cancelled

print(taskOne.await())

}

launch {

print(taskTwo.await())

}

}

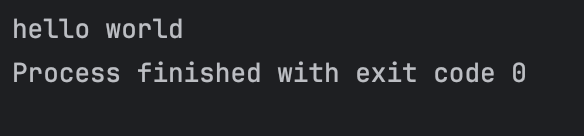

The above is one of the more complicated “hello world” programs.

We create a coroutine context as usual.

We then launch an async job which returns a Deferred. The job immediately yields so the next coroutine can run before returning “ world”.

We then launch another async job. This job simply returns “hello”.

Instead of awaiting the results directly, we await them inside another coroutine so they don’t suspend the current coroutine. Otherwise, we would have simply printed the results in the order we awaited them.

See here for the full code.

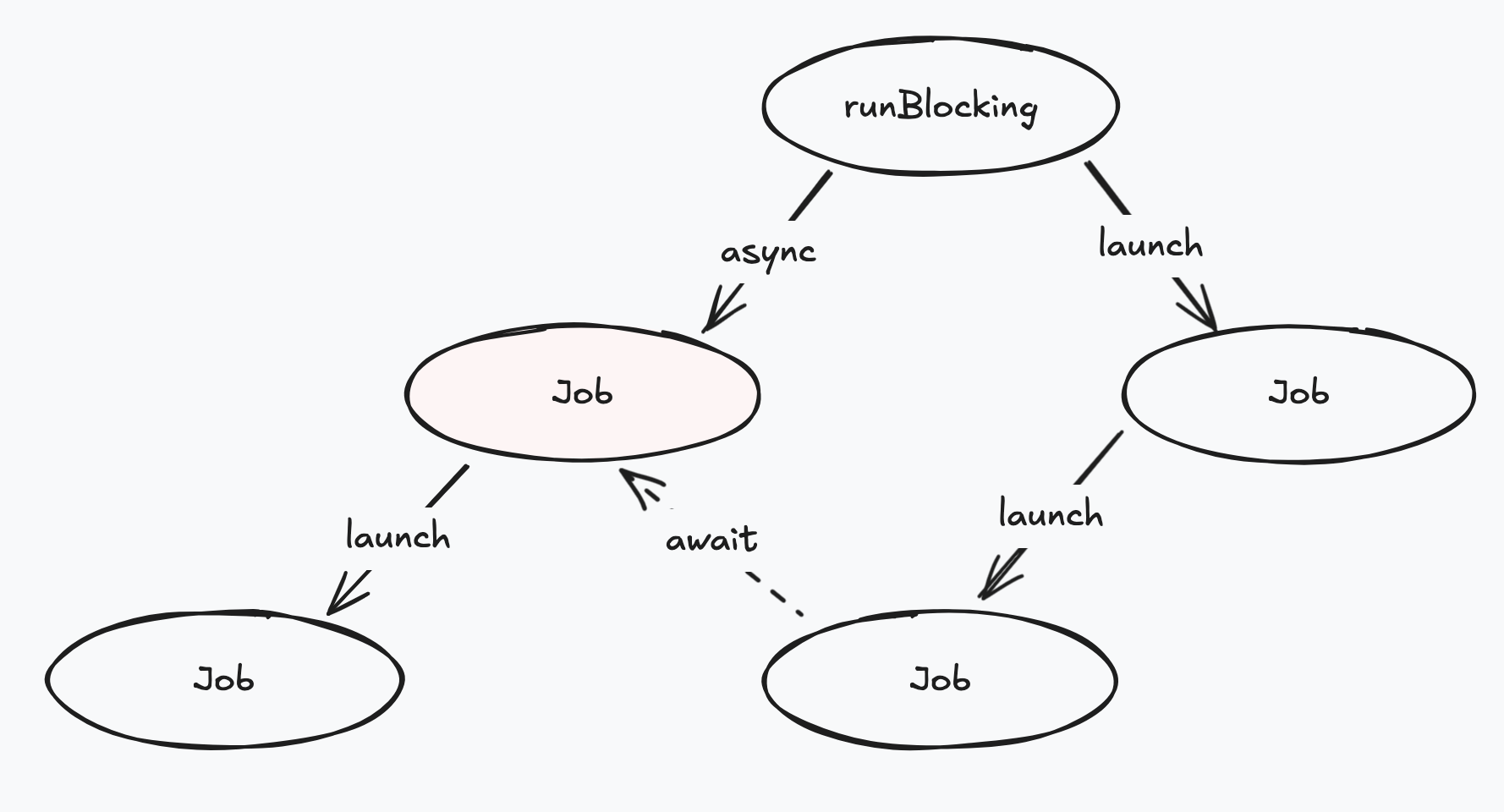

Structured concurrency

Kotlin uses structured concurrency to manage concurrent tasks. This ensures Jobs are not lost and avoids memory leaks which makes concurrent processes safer to manage.

Within a coroutine context, coroutines are managed in a hierarchy such that parent jobs can keep track of the state of their children.

runBlocking is the first step in introducing structured concurrency. runBlocking creates a coroutine context which bridges the gap between blocking (serial) and non-blocking (concurrent) code.

This function blocks the current thread until all Jobs within its scope have completed.

runBlocking does not preserve the existing coroutine context so avoid scattering this throughout your code. Typically this is only run at the entry point of a program.

coroutineScope is similar to runBlocking however it maintains the current coroutine context when creating new Jobs. Unlike runBlocking, coroutineScope doesn’t block the underlying thread, it only suspends the current coroutine.

New coroutines can be created within these scopes (via launch and async). Kotlin will keep track of these jobs so that the parent jobs will not complete until all its child jobs have completed.

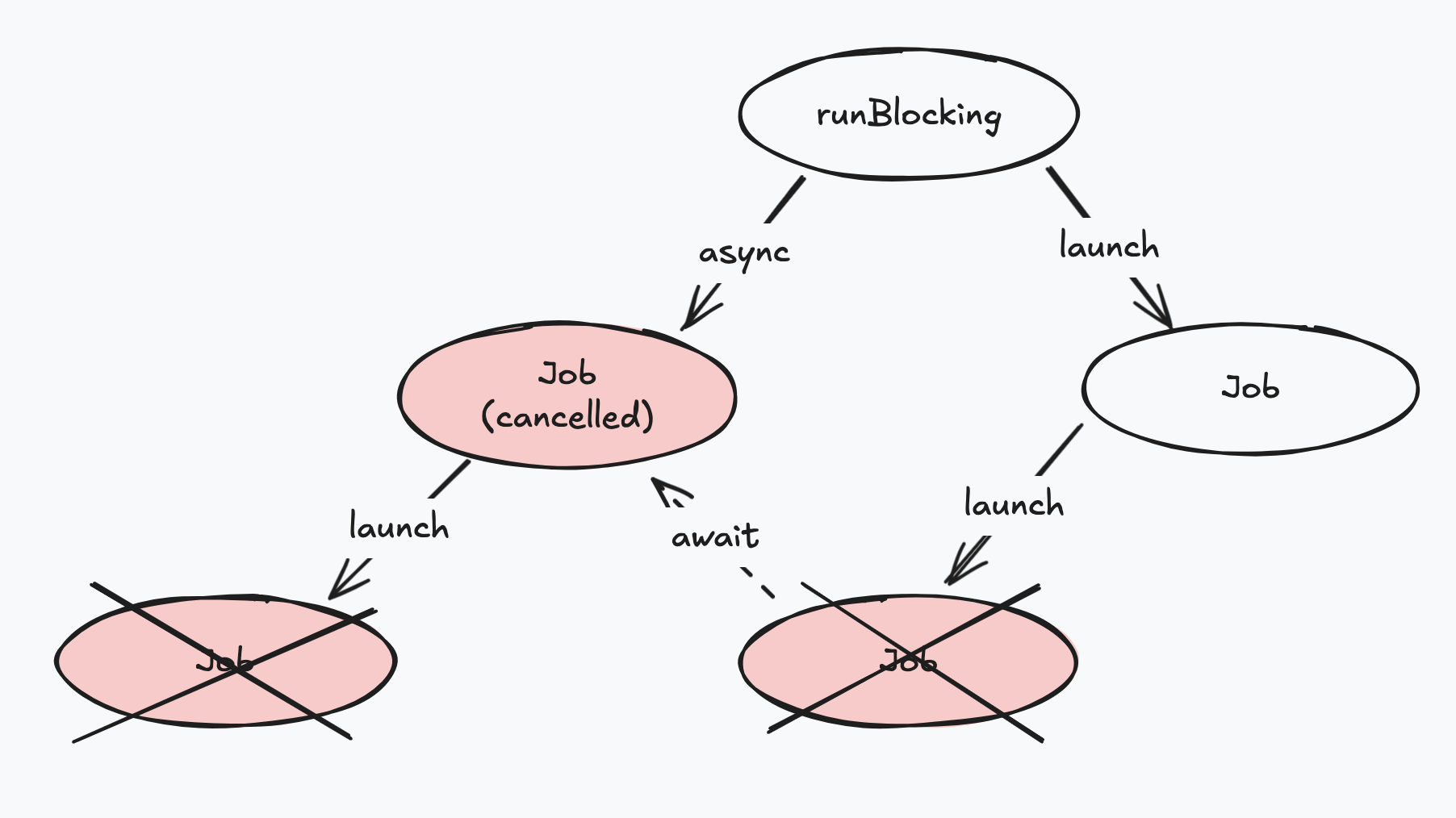

Additionally, if a job is cancelled, so will its child jobs, or any jobs dependant on its result.

Conclusion

Hopefully this article gave a better understanding of how concurrency is enabled in software systems and how to leverage it in your Kotlin projects. To summarize:

- Threads are managed by the kernel

- All processes have at least one thread

- coroutines are managed by the process they run in

- coroutines can be suspended so the underlying thread can execute other coroutines

- use runBlocking to create a coroutine context

- use coroutineScope to create an inherited coroutine context

- use launch to execute a task concurrently when you don’t expect a result

- use async to execute a task concurrently when you do expect a result

Finally, while Kotlin provides a great framework for safely adding concurrency to your system, introducing concurrency always comes at a cost, and so should be used with careful consideration of the operations being performed.

Further reading

This only scratched the surface of concurrency and the tools available in Kotlin.

You can also enable parallel operations by defining Dispatchers, pass data between coroutines using channels, set timeouts on operations using withTimeout, and asynchronously stream values with Flow.

We also didn’t touch on the other concurrency pattern available in Kotlin, known as Reactive Concurrency. That deserves its own article.

For further reading I would highly recommend:

- The official kotlin docs for exploring all the library features which covers those other topics this article didn’t get to

- Coroutines: Concurrency in Kotlin YouTube video by Dave Leeds for a great illustrated explanation of Kotlin coroutines

- Kotlin Coroutines Series by Rock the JVM which dives a little deeper into the code

- Grokking Concurrency by Kirill Bobrov for a more theoretical understanding of concurrent systems, problems that are introduced by concurrency, and patterns to address them. As well as techniques for breaking down a problem to identify potential areas for concurrency